Build to Compete: How Long to Become a Bodybuilder?

Becoming a bodybuilder blends time, consistency, and smart planning — it’s less a fixed deadline and more a progression through stages of learning, adaptation, and refinement. Whether your goal is to fill out a frame, step on stage, or simply master strength and physique, a realistic timeline helps set expectations and keeps motivation steady. For foundational reading on broad fitness principles that support this journey, see unlocking your fitness potential which covers essential habits that complement bodybuilding goals.

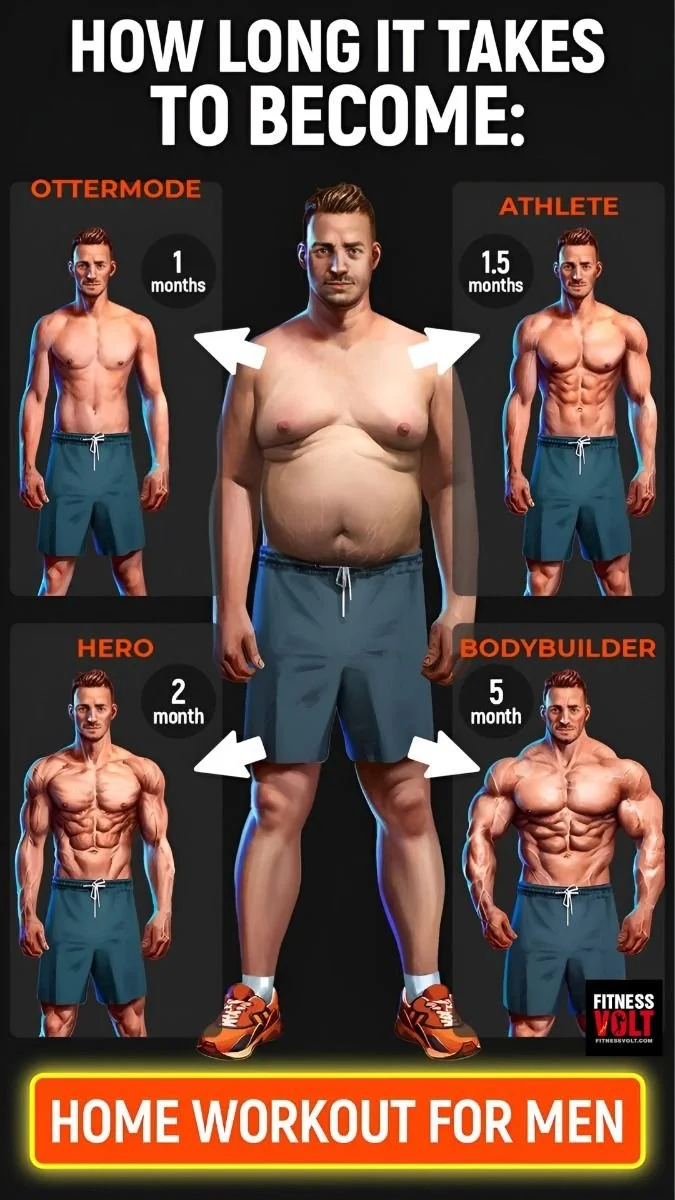

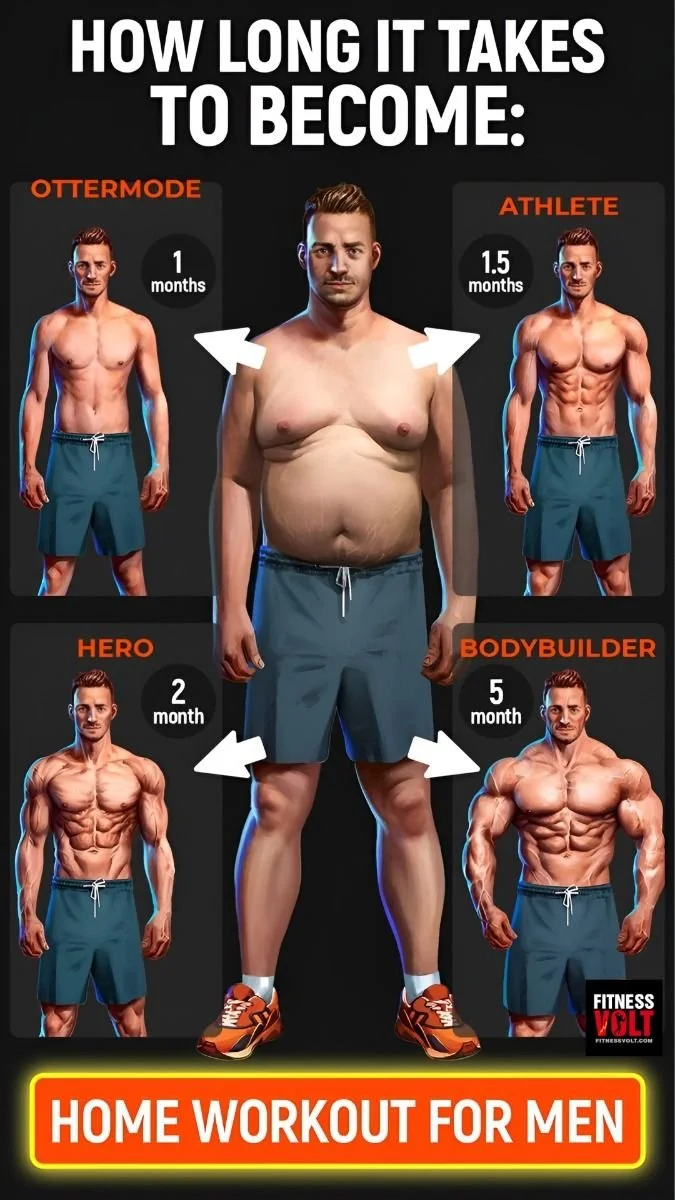

Overview: realistic timeframes

- Beginner visible changes: 3–6 months of consistent training and nutrition will produce noticeable strength and size gains for most beginners.

- Intermediate progress: 1–2 years to build substantial, sustainable muscle after mastering form, progressive overload, and diet.

- Advanced/competitive level: 3–5+ years of focused training, contest prep, and refinement to reach a stage-ready physique for natural athletes; longer if aiming for elite levels.

Factors that change the timeline

Genetics, age, sex, starting body composition, training quality, sleep, and stress all influence speed of progress. Someone with favorable genetics and good training experience may show dramatic changes in a year, while another person may need several years to reach similar development. Realistic planning accounts for plateaus, needed recovery, and life interruptions.

First-year focus: learn and build

Your first year should emphasize technique, consistent strength progression, and dialing in nutrition. Prioritize compound lifts (squats, deadlifts, presses, rows) and progressive overload. At this stage, you can often gain both strength and muscle simultaneously — the best period for accelerated improvements. For core habit-building and targeted training strategies, consider techniques from the how to get a slim waist guide to refine posture and midsection control that complement a bodybuilding physique.

Intermediate approach: specialization and variety

After year one, gains slow and require smarter programming: periodization, targeted hypertrophy work, and recovery management. Use phases of volume-focused hypertrophy, mixed with strength blocks and occasional conditioning. Tracking progress, learning exercise variation, and addressing weak points becomes essential. Incorporating high-intensity interval approaches sparingly can aid conditioning without sacrificing mass — see ideas from the HIIT workouts guide for balanced conditioning options.

Nutrition and recovery: critical throughout

Muscle growth needs a modest caloric surplus with sufficient protein (commonly 1.6–2.2 g/kg bodyweight), timed carbohydrates for training, and fats for hormones. Recovery is equally important: aim for quality sleep, stress management, and scheduled deloads. When prepping for visual goals or competitions, clean, structured phases like short resets can help control body composition; resources such as the 7-day detox challenge printable guide can be adapted as a short-term reset to remove processed foods and re-establish disciplined eating, though long-term sustainable nutrition is the priority.

Competition timeline and prep

If your goal is competing, add 3–6 months of contest prep after reaching a solid mass base. Prep involves a calorie deficit with preserved muscle via high-protein intake, strategic cardio, posing practice, and peak week tactics. Novice-level competitors often enter shows after 1–3 years of focused training; expect longer if chasing elite conditioning.

Measuring progress and staying motivated

Use multiple measures: strength numbers, tape measurements, progress photos, and how clothes fit. Small, consistent wins — hitting weekly training goals, tracking macros, improving lifts — build toward major milestones. Work with a coach for programming or nutrition when progress stalls or when refining contest strategies.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Chasing quick fixes: avoid extreme diets or shortcuts that sacrifice health and long-term gains.

- Overtraining: more isn’t always better. Prioritize quality sessions and recover fully.

- Ignoring weak points: balance aesthetics and function by addressing lagging muscle groups and mobility.

- Neglecting consistency: sporadic effort extends timelines dramatically.

Conclusion

Becoming a bodybuilder is a multi-year commitment shaped by your goals, consistency, and willingness to learn; for a thorough primer on starting the bodybuilding path and what to expect early on, review this comprehensive starting guide to bodybuilding.